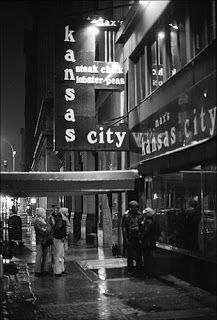

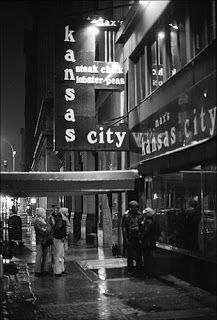

There were comings and goings outside Max’s. Yellow cabs lined at the curb, groups clustered about the door, the smell of weed on the heavy night air. The big black sign, L shaped with fat white letters hung above the awning, over the comings and goings and hangings out: Max’s Kansas City, Steak Lobster Chick peas. In the summer of ’72 it was still the place to be someone, or better still, someone else, to measure yourself, see who was who, and why they came to say, I cannot stay, I must be going.

The window framed a Chamberlain sculpture of crumpled auto parts – colorful bits of Chevys and Buicks in a mash up of anguish and culture or something like. Pull open the big glass door and loud music was in your face.

“Gor-blimey it’s the Limey.”

“Hey, Suzy. You’re leaving?”

“Going out for a smoke.” She rolled a fat joint between her fingers. “Wanna come?”

“Later,” I said.

A

fter the sulfurous yellow streetlamps Max’s was red. The tablecloths were red, the napkins were red, the lights were low. The long bar was on your left and beyond it tables and booths, the kitchen, and beyond there the gender bender backroom. On the wall opposite the bar, over the jukebox, there was an artwork by Donald Judd, machine-made out of shiny brass. Something mathematical is going on there between the box like forms and the spaces in between. What it is, I couldn’t say. ‘What’s going on?’ I couldn’t say. ‘What’s going on?’ Marvin Gaye’s voice swells from the jukebox filling the spaces in between and all about.

“Behind you. Comin’ through.”

Lithe young waitresses in black minis and tiny red aprons slid back and forth through the velvet smoke hefting trays, heavy with steaks and liquor, over the heads of the young, noisy crowd. The owner, Mickey Ruskin, stood puzzled and distracted in his charcoal pants that never reach his ankles. He was about to go... “What?”... about to go... “What?”... He had drug issues of his own.

The early diners were headed home, the graveyard shift settling in as I pushed through the crowd at the bar. Neil Williams, painter, John Chamberlain, sculptor, fixtures in their usual spot against the rail by the fender-bender opus. Like others they had traded their art with Mickey for tabs, and were busy drinking his finest liquor.

"Hey, Brice. Hi David."

Those guys always sat with beautiful women. Lawrence Weiner and Garry Owen were at a table further back, I made my way over to say hello.

“Hello, again.”

A woman spoke to me as I passed. Elegant in white, middle-aged, with the look of money about her. I said "Hi", but only had eyes for the gorgeous waitress who was known to be choosy.

“Hi Ellen,” I said.

She flung a red tablecloth flapping through the air. “Hi” she smoothed it down. Oh, that deviant smile it made me crazy. She never chose me. Other tables were cleared as I passed. Gnawed bones and mounds of luminous mint jelly on clattering plates stacked and whisked out of sight. Lou Reed’s latest, Walk on the Wild Side, replaces Marvin Gaye on the jukebox.

“Siddown,” said Lawrence, a young artist like myself. “What’s new?”

Hanne Darboven, a young German artist with perfect manners, sat bolt upright between the two slouching men. Their full beards swept the table. Max’s is a hairy place.

“Got an eye for Ellen, eh?” Lawrence grinned.

“Ya. We did saw you." Hanna's watery blue eyes were alive. "You do wear your heart on your coat.”

“That’s not his heart,” laughed Garry Owen. “You gotta go lower.”

Couldn’t deny it, wouldn’t try. I looked back toward the bar. “D’you know who that is? The woman in white, just leaving.”

They craned their necks as a willowy black waitress came to our table

“I’ll take another armagnac,” said Owen. “You mean the Widow?”

“Yeah. In the white,” said Lawrence. “Applejack, thank you.”

I took a beer. Days before the woman in white had stopped me in a gallery with the words: ‘You look like my dead husband.’

“Knox?” Owen scoffed, incredulous. “Nah, you don’t. Nothing like. It was pick-up line.”

Gary Owen was older, straddling the generations of Beat and Hippy. A painter, caught between Abstraction and Pop, he’d had success and lost it. Now he drank.

“You knew him?” said Lawrence. “What was his name ... Stanley, Stanford?”

A woman’s boisterous laugh exploded at a nearby table. Gloria Bicce was a loud fixture at Max’s. We glanced at her then turned to Owen.

“Yeah, Cecil, Sidney, some damn thing, but he was known as Badger,” he said, pulling at his beard. The name Badger fired some dormant synapse in me while he talked, I knew the name but couldn't think why.

“I was in a Happ’nin’. You know, early sixties, down on Great Jones Street. She was in it.” Gary Owen flicked a thumb toward Gloria loud. “Lotta fun those Happ’nin’s, erotic, lotta naked flesh, lotta groping." He couldn't resist a gurgling chuckle at the thought. "One night, after the show, I’m standing there buck naked, ole glory wavin’ in the wind, when this babe from the audience comes up to me. Uptown money written all over her, one of them Jackie Kennedy hairdos, early thirties. I don’t have to ask what she wants she’s starin’ right at it. Cool as you like, she invites me back to her place. ‘Come as you are,’ she smirks.”

The silky waitress set drinks on the table while we salt and peppered his memory on our separate plates.

“She has a cab waiting when I get out," he went on. "And a guy. ‘This is Badger,’ she says. ‘My husband.’ The fuck! You kiddin' me? He’s a Wall Street suit. Nixon with thinning hair, cufflinks and tie. I mean, come on, cufflinks? At a Happ’nin’? I’m thinking, What's up with this, man, when laughing girl,” another thumb at Gloria, “joins us and I see we’re gonna party.”

“Ach.” Hanne raised her eyebrows, following along seriously like she was taking dictation. She held her cigarette poised like a syringe at the tips of her fingers.

“So, the wife pulls me into a separate cab and gives the driver a Sutton Place address.”

“Fancy,” said Lawrence.

“Shoulda seen it, man. Fuckin’ A. Un-real, even had its own elevator. And Gloria’s already on the couch ballin’ the Badger.

Ballin’ the Badger? Hanne’s face crimped with curiosity. You could almost see the translation going on word for word. And it wasn’t just the words; the whole culture left her in need of a dictionary. Her pale blue eyes searched Owen’s face for clues. She was determined to get to the bottom of this. Bolt upright with the blonde hair close-cropped and the German accent you might think her some kind of ubermensch. But no, she was just tense – tight as a drum at Valley Forge.

“Ya, ya. Vas?”

The noise swelled as more drinks arrived. Janis Joplin’s Ball and Chain, shook the place. A woman danced by on her way to the can. Gloria's deep-throated roar cut through it all. Her head thrown back, swinging from the arm of her bashful young man; lunging backward, laughter rippling her flesh, till one of her large pillowy breasts flopped from her open shirt.

“Escape!” screeched her friends.

In no hurry to corral the beast, howling, she crushed her flummoxed boy into her bosom. Her honking friends fell on one another in delight.

“Zeitgeist, man,” Owen watched with pleasure. “She was pretty once. Before the drugs. That hair used to be so silky.” He smiled and shook his shaggy head. “Zeit-fucking-geist.”

“And so ..?” Impatient Hanne. “And so?”

“So.” Owen gave a whaddaya expect kind of shrug. “The 'Widow’ and I got it on ... It’s going great ‘til Gloria wants in. She’s pushing me out, taking over.”

“What happened to Badger?” said Lawrence.

“Groping, groping me! Gloria’s set me up, don’t ya see? Imagine that, sex with Richard Nixon.”

“Oooh. Too political,” I cringed.

“Absolutely ... metaphorically speakin’ I’d like Richard Nixon to suck my dick. But in reality it was a real turn-off.”

“Watch your back. Coming through.”

The tables all around were filling up. Animated talkers side by side, front to front and back to back. Carl Andre had come in with Poppy, they were standing talking to Dorothea and Richard at a nearby table. Andre had his hands pushed way down into the pockets of his blue coveralls. With matching jacket it was the uniform of the working man. Its style and its politics suited him. He never wore anything else. His large head and full beard and more than shoulder-length hair gave him the look of Walt Whitman, but his wit was more often delivered in the dead-pan drawl of W. C. Fields.

The willowy waitress put another armagnac in front of Owen and ducked away. The sight of it cheered him up.

“Art-Workers Against the War,” Poppy told us where they had been as she sat. She and Andre were part of a politically active group that kept a close watch on the Vietnam War, organizing political theater and demonstrations. She was very young, twenty-one at most, with Scandinavian features and long blonde hair. She took a deep red pack of Pall Malls from her purse and put them on the cherry red tablecloth.

Badger. I sat there chafing my memory to find why the name was familiar. I mean Badger’s a name you remember. Then I got it. Sabena Airlines, a six-hour flight seated next to a middle-aged Belgian bookseller. We’d exhausted polite chit-chat and got into Inspector Maigret mysteries by Georges Simenon the Belgian writer

“He liked the ladies, right?” I said.

“Oh, yes. Amazing womanizer.”

It brought up someone he knew in the Belgian Congo. He’d been there as a young civil servant during its transition to independence. He still felt guilty, still ashamed of his country’s abuse of the colony. Especially Lumumba.

“Remember Patrice Lumumba?” I said.

“Remember Lumumba doin’ tha’ rumba.” Gary Owen drummed on the tabletop.

“Wasn't he assassinated?” said Poppy.

Firing squad, ordered by the Belgians. The bookseller, full of remorse over his country’s role in it, talked of an American he knew. A man called Badger Knox. It seemed personal, more to it than he was telling. He said Badger was everywhere – Leopoldville, Stanleyville, pulling strings, a real operator. There were factions within factions, breaking out every day, a civil war tearing the country apart. Everyone wanted their own kind of independence.

“And Badger was in the thick of it, conniving.”

“Was he CIA?” said Poppy.

"Doubt it,” said Owen.

“War profiteer,” said Lawrence. “Another Harry Lime.”

The Belgians were sending supplies down there: emergency food, medical needs, military personnel, armaments. What Badger Knox saw was planes full of cargo landing, empty planes going back. He knew the Congo was rich in coffee and copper, diamonds and cotton. But the place was in chaos, armed conflict; they can’t sell or move what they have. But he can. He’s on nobody’s side but his own. He makes deals all over, buys for next to nothing, or just takes it, and ships back for free.

“He made his fortune.”

“I shoulda fucked the crap outta him!” Garry Owen laughed.

Carl Andre pulled out a chair as he looked about stroking his beard. Did all men with beards need to pull at them? He sat down with a sigh.

“A sultry night. Not fit for man nor beast.”

For a sculptor, still in his mid-thirties, he’d had a lot of success: prestigious shows at the Guggenheim and major European museums – even had an entry in the Columbia Encyclopedia. He was also a poet, widely read, verbally unpredictable and combustible. He could quickly flip from a jovial Falstaff to a bad tempered Marx.

“I’m thinking of having gills implanted.” He was Falstaff tonight. “So, here we are again.” Andre’s gaze made another slow panorama of the room. “And again and again.”

“We’re ‘ere because we’re ‘ere, because we’re ‘ere.” I offered the ditty from the war to end all wars. Here because we didn’t want to be left out.

“I cannot stay,” Andre changed the tune to a Groucho Marx song, ‘I came to say ... I must be going.’... So,” he said calling for a wine for Poppy, a Remy Martin for himself. “Anyone else – my treat.” He was always generous.1

“Hey, Mickey.” A voice yelled the length of the bar. “A coupla queens’ve locked themselves in the bathroom. I gotta take a piss.” Mickey Ruskin stalked, bent forward, an ostrich on the go. “What now? What the fuck?”

“Remember when the widow found Badger in bed with a guy?” said Poppy. “All the tabloid scandal.”

“Why would she care,” I said. “Doesn’t sound like her.”

“She didn’t care,” said Poppy. “It was the other guy who went to the tabloids.”

“He was after the money,” said Andre.

“It’s always the money,” said Lawrence.

“A few months later he was dead,” said Poppy.

“By what?” said Hanne.

“Seizure? Maybe. Heart attack? It’s fuzzy now,” said Poppy looking about. “D'you remember?”

We shrugged. Who knew. Time passed.

“They lost his body, I remember that.” Andre giggled into his cognac.

“Lost?” said Hanne. “Where?”

“If they knew they’d have found it. They misplaced it! Shipped it out West for burial, but the airline lost it."

"That's right," said Lawrence. "They thought they found it in Bermuda ... turned out to be a large dog bound for Israel."

"The widow said the body left a stain on the sheet,” said Poppy.

“Stains remain,” I thought.

“Sten?”

|

Max's Kansas City photographer unknown

A typical letter from Hanne Darboven

Hanne gave us the wide eye, looking from face to face. None of us knew German. Lawrence tapped the damp ring on the tablecloth left by a sweating beer bottle:

“Like that.”

“Ach, so.”

“I love the faint remnants, ghosts,” I said. “There’s a wonderful staircase imprinted on the wall next to a torn down building near me.”

“Near the Square Diner? Yes,” said Poppy. “And that barely visible faded sign for Mathew Brady’s Civil War Photography Studio.”

“I Like the skeletal pilings of the old piers in the Hudson,” said Garry Owen worrying his glass again.

A fondness for stains and their shadowy existence drew us in. Impressions left about the city, palimpsest history imprinted in fading memories.

"Palimpsest, man? The fuck? You guys think too much," said Owen.

"Don't worry," Lawrence laughed. "We'll never accuse you of that."

Andre liked more solid stains like New England boulders as crumbs from the Ice age plate. And:

“I like the scars from Con Edison roadwork,” he said. “Roads are the perfect sculpture. They’re neither phallic nor intrusive.”

So the fitted sheet of Sutton Place became the Shroud of Turin. The after-burn on the launch pad. I thought of Badger’s ascending soul, off to Max's in sky. I only came to say, I cannot stay, I must be going.

A tag team of drag queens paraded by to the backroom with amphetamine hoots and squeals. A colorful band of silconed shape shifters – Jackie or Holly or someone else staggering on high heels. “Jackie is just speeding away, thought she was James Dean for a day” Gloria joined in with Lou Reed, very loud. You wouldn’t call it singing.

“Give it a tune.”

“Go fuck yourself Garry Owen!”

Our willowy waitress delivered Owen’s armagnac. The narrow features of her long Ethiopian head then turned to the others.

“I’ll take a Heineken,” Robert Smithson appearing beside her pulling off his jacket.

“Same check?” She nodded.

“Just saw Beyond the Valley of the Dolls again,” Smithson threw a pack of menthols on the table. He took the conversation before taking a seat, hovering over his thought with sly pleasure. “Totally mannerist. Complete summation of the sixties.”

A year earlier Robert Smithson had finished his monumental earthwork, Spiral Jetty. Already it was the most famous sculpture in the country. Photographs of him show a serious man with a spill of lank black hair falling over aviator style glasses, his face scarred by adolescent acne. But the best picture of him is Alice Neel’s portrait. In it he’s young and skinny in a rumpled black buttoned up suit. One leg is hiked up across the other, his shoulders hunched, his expression one of glaring concentration. The paint is loosely, almost crabbily, laid on in colors you might find in old cans at a shipyard. She’d worked his face so much, stabbing and scraping, she left an angry mess that exposed his brooding intensity. He’s leaning on your thought.

“The movie ignores all that Woodstock bullshit.” He spoke to his cigarette pack as he dashed one loose and put it in his mouth. “Goes straight for the flabby white underbelly of polyester: perversity of flesh, big babes, drugs, violence, rock ’n’ roll, soft-core porn.”

“Ah, Bob,” said Andre. “You love the very squalor of squalor.”

“Reality. Everything moves toward disorganization.” Smithson lit his cigarette and scowled. “Entropy.”

He was the happy outlaw of discomfort. Anger at passivity was good. Something he said obviously amused John Baldessari at the next table because he leaned over and responded. Whatever it was didn’t please Smithson.

“This is New York,” he snapped. “We’re not interested in jokey California art here!”

He could be harsh but not dull. In less than a year from this hot summer night, Smithson would go off to Amarillo, a place that likes to call itself the real Texas. He was there to scout sites for a new earthwork – the Amarillo Ramp. On July 20, 1973, he got into a small plane with a local pilot and took off to survey the area. Rumor had it that they dropped acid before take off. Who knows? He liked to live on the edge. Rumors are rumors. At some point the pilot lost control of the plane and it crashed killing them both. Robert Smithson was 35 years old.

In the mourning months following his death, his widow, Nancy Holt, came to remember him as that skinny young man in the painting. She looked around and decided I was the only one skinny enough to take his clothes.

“Can I clear these glasses? You finished with that?”

The busboys cleared. Like nurses changing bed sheets it brought a temporary quiet as they moved in and out taking glasses, changing ashtrays. Time to use the cramped bathroom where shemales hogged the mirror. A moment to look around, see who’d come or gone. Scores of artists, young and old, hung at Max’s: visual artists, musicians, writers, performance, filmmakers. Some I knew, far more I didn’t, either by name or by sight. All here because we’re here. Occasional ly there’d be a buzz of glamour created by some celebrity, or Andy Warhol cruising the room, ”Ooo. What’s his name?” or de Kooning “Ech. My age – always wid de creaking and de farting.” But most nights the superstar was ambition and the place itself.

“Do you have cigarettes?” Hanne asked the busboy.

“Am not a waitress. Machine’s up front, near the juke.”

“Is our waitress that one?” Hanne still sat rigidly straight.

“Well. Just one more cognac,” said Garry Owen, who didn’t.

“She was an Abyssinian maid,” I said.

“Aha ha. Yes, indeed.” Andre came to life, his eyes lit up. “And on her dulcimer she played.

“In Xanadu did Kubla Kahn?” said Smithson. “Always sounded like Vegas, to me. Bugsy Segal as Kubla Kahn in the desert. All those underground caverns, measureless to man, going ‘Down to a sunless sea.’”

“I won a hundred and sixty-two bucks in Vegas,” says Garry Owen. “at the Sands.”

“I do not like sand.” Hanne was firm.

“A lifeless sea of nothingness,” said Smithson. “Underground deliquescence,”

“Deli what?” said Poppy. “Deliquescence?”

“Over indulgence of chopped liver,” said Andre. “It killed Badger Knox.”

“Nothing killed him,” said Smithson. He hunched forward, deadly serious. “Badger Knox never died he melted away. Deliquescence means absorbing moisture from the atmosphere ‘til you turn to water. Badger was a sponge. He grew paranoid when Mobutu took power in ‘65. Something had happened in the Congo he never talked about. He feared retribution. According to the widow Badger couldn’t stop crying. Water everywhere. He liquefied. Slowly dissolved. He never died a corporeal death, he died of convenience ... melting away ... engineered the premature evaporation of his soul, and lost the body Badger on Trans World Airlines, first class. His vaporous spirit transmigrated to Texas where the dry desert air distilled it.”

Smithson took a swig of his beer and savored the nonplus look on our faces.

“Dah, bullshit!” Andre roared. And we laughed.

A late, straggling dolled-out superstar went clattering through to the backroom blowing kisses. Plucked her eyebrows on the way – Lou Reed on the juke for the twentieth time that night – Shaved her legs then he was a she. She said, ‘Hey babe take a walk on the wild side.’

4.00 a.m. “Is Late,” said Hanne

The bill was split and paid, mostly by Andre. The table left for the busboys, strewn with glasses, crumpled cigarette packs, misunderstandings, bruised egos, overflowing ashtrays and unfinished thoughts. The thinning crowd had quieted to murmurs. Even Gloria’s drug fueled table was subdued.

Out into the humid air to deliquesce. I started home with afterthoughts, what might have been said, if only what was said wasn’t said. Did Badger die or become someone else? The streets were empty, no one to be seen. Only late-night traffic moved through. It came in waves. Held up at the light. The street went quiet. Only distant sounds...a horn, a mending plate banging. Quiet under the sulfurous haze of street lamp night. A new wave, their taillights bobbing, hit the plates and potholes of outrageous fortune. I, too, felt dented. A displaced person by choice, living an invented life. These other artists had a sense of place I didn’t share. It wasn’t bred in the bone. I felt the tremor of seismic questions. Was there ever a way to know? Explaining myself to myself it was clear, no matter how many pairs of blue jeans I bought I would always be an immigrant. Still, stains remain.

Spiral Jetty by Robert Smithson

This story is from YOU HAVE TO BELIEVE IT TO SEE IT

Memories of Conceptual Art by Michael Harvey

|